Weekly Market Update by Retirement Lifestyle Advocates

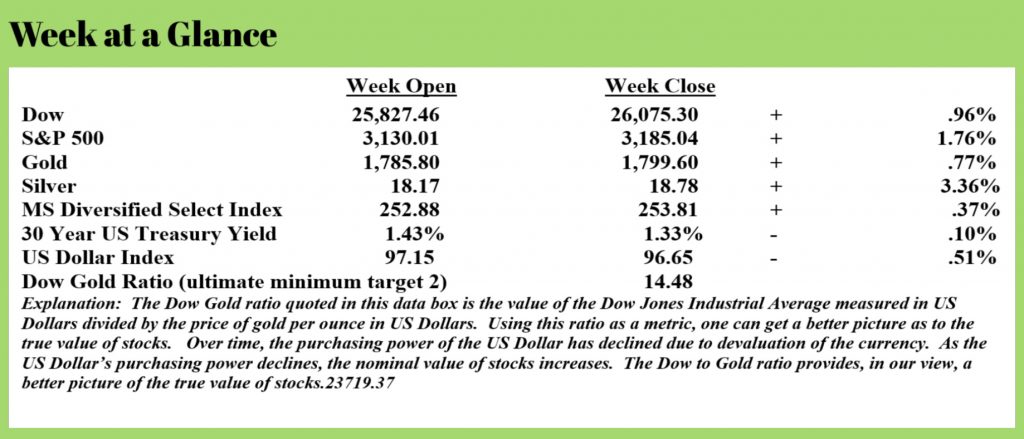

All markets advanced last week and the Dow to Gold ratio remains between 14 and 15.

Here in the pages of “Portfolio Watch” each week, we present evidence as to where the financial markets and economy may be going in light of the extreme economic conditions that now exist.

We can learn much about where we are headed economically and financially by studying similar times in history. That’s the focus of this week’s “Portfolio Watch”.

We’ll compare 1929 with today’s economy.

While there are many similarities, there is one striking difference – the money. Up until 1933, the US Dollar could be exchanged for gold at a rate of $20.67 per ounce. Today, the US Dollar is unbacked; meaning there is no limit to the quantity of fiat currency that can be created.

In the early 1930’s prices tended to be more stable; today prices are rising in many categories.

But there are many similarities. In 1928, President Herbert Hoover was elected as the economy was roaring. However, in 1929, Congress passed the Smoot-Hawley Act in response to a contracting US economy, which imposed large tariffs on imported goods. The idea was to protect US farmers and manufacturers from foreign competition. The country’s mood was nationalist and government intervention in trade was welcomed. A lot like today.

For context, the boom of the 1920’s occurred largely because of Fed policies. The Fed was formed in 1913. Benjamin Strong, who was the Chair of the Federal Reserve in the 1920’s pursued easy money policies which created a boom and then a bust as always happens.

Hoover attempted to reflate the economy. He called a series of meetings with business leaders and implemented policies to attempt to keep consumer spending going but he neglected to also focus on production without which consumer spending has to be limited. Turned out to be a big mistake.

Franklin Roosevelt won a landslide victory over Hoover in the election of 1932 as banks were failing, farmers were revolting, and unemployment was soaring. Again, not all that dissimilar to today’s economy.

Alasdair Mcleod, past guest on our radio program compares (emphasis added):

Roosevelt then delivered his inaugural address, which included the famous line, “So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” His speech was followed by the Hundred Days, the first time a president had set such a schedule.

In Britain, Rishi Sunak, the new Chancellor, is now pursuing his version of a Hundred Days announcing subsidies and new support as the occasion demands, financed by monetary inflation. Admittedly Sunak remains a free marketeer but has yet to prove his measures are temporary. Meanwhile, President Trump is destroying his administration’s finances in an attempt to contain the economic fallout from the coronavirus in his election year.

They say that repeating a failed action in search of a different outcome is a sign of madness. Hoover and Roosevelt were pioneers of today’s failed economic policies and it is their post-war successors who are arguably certifiable. But the problem is deeper than that, with the public voting for the same failed policies, so even an economically literate politician has to deliver solutions in that context. It is what makes history repetitious. Instead of economics, psychological factors drive politics, including the public desire for the state to provide easy solutions to economic and personal difficulties. But the lesson from the Hoover era is that we stand on the precipice of an economic collapse as a result of a combination of excessive credit creation in the years before and the introduction of trade tariffs. And that was before the coronavirus was added to this lethal mix.

The psychology suggests that this time the politicians and the monetary authorities will pursue much the same course as before, even more aggressively. So far, the evidence supports this thesis, and it allows us to anticipate mistakes yet to be made.

History does repeat itself. It appears that it is repeating itself this time too.

At the onset of the Great Depression, bank failures were rampant. Once again Mr. Mcleod relates (emphasis added):

But when the public began to withdraw cash in increasing amounts this false liquidity was exposed. The initial banking panic began in November 1930 in Tennessee when a correspondent network in Nashville collapsed after the Bank of Tennessee closed its doors, forcing over 100 institutions to suspend operations. And as the contraction in bank credit continued, additional correspondent systems imploded. That was only the start of it. The Bank of the United States in New York in December was followed by a new banking crisis in Chicago the following June, this time involving real estate. In 1932 over 2,000 banks closed, and in 1933 a further 4,000.

With a fundamentally weak global banking system, over-leveraged and virtually guaranteed to collapse as current financial and economic conditions deteriorate, a new banking failure could make the first wave of bank failures in 1930 Nashville look like a vicar’s tea-party. The failure of just one major bank anywhere in the world is likely to degenerate into a widespread panic because global regulation has ensured they all game the system similarly and they all share the same weaknesses to a greater or lesser degree.

In another potentially fatal error, following the Lehman crisis the G-20 agreed to new rules designed to ensure that the costs of future bank failures are to be carried by bondholders and large depositors as well as shareholders, and not governments. Fortunately, this bail-in route is intended to be optional, but there is a risk that in a widespread banking crisis one or more of the G-20 members will go down the bail-in route, probably for banks not on the G-SIB list but smaller and no less significant banks. With some bailing-out and some bailing-in, simple nationalization and preservation of all customer deposits becomes less likely, prompting a collapse not just in the banks bailed in, but panic in all bank bonds and major deposits which would otherwise be protected in a clean bail-out.

Putting the bail-in uncertainty to one side, instead of a series of bank failures between 1930-33 today’s global banking interdependence suggests one major crisis is more likely, which arguably has already started given the liquidity injections that have taken place since last September, commencing in the repo market.

We have repeatedly warned of the weakness in the banking sector, first discussing the repo market being propped up in October issues and more recently with the reporting of banks operating under a zero percent reserve requirement since March of this year. There are many similarities between the banking system of the early 1930’s and today. However, due to the fact that the US Dollar is unbacked today, the problem will have to be worse today. And, should the next banking failure be addressed with bail-ins, it’s possible the depositor’s assets could be at risk.

If you’ve not yet checked the safety of your bank or come up with a cash diversification plan, we’d strongly advise you to do so. We can help you do this if we haven’t already. Just give the office a call at 1-866-921-3613.

The bottom line is this.

Governments are making the same mistakes as they made 90 years ago when putting forth policies to deal with the current environment. Mr. Mcleod concludes (emphasis added):

As was the case between 1930—1933 we can be almost certain of a banking crisis. This time it will be global and almost certainly will require banks to be taken into public ownership. The cost will be immense, and it will be paid for by inflationary means.

The scale of it will mean an unprecedented destruction of wealth — hardly the basis for economic recovery. At the same time statist preservation of existing production for fear of unemployment will hamper, not help economic recovery; and, so long as fiat currencies retain any exchange value, there can be no economic revival.

Indeed, the most important difference from the 1930s is the money, which could well collapse entirely. Guided by the pre-Keynesian economic theory of the Austrian school, of the economic consequences we can be certain. The political consequences, in the long run, can only be guessed.

It’s our belief that most of our readers are utilizing the two-bucket approach to managing assets as outlined in the book “Revenue Sourcing”. If you are not, give the office a call and we’ll help you get started.

Thank you for your referrals!

If you know someone who might appreciate this publication, invite them to subscribe for free at www.RetirementLifestyleAdvocates.com. Or, just forward your newsletter e-mail to them.

This week’s RLA radio show is now posted at www.RetirementLifestyleAdvocates.com. This week’s program features an interview with Karl Deninger.

Mr. Deninger is a returning guest and an expert in the area of healthcare financing. Tune in to hear his shocking prediction as to the future of Medicare.

There are also other resources posted there as well as all past podcasts of the radio program.

“My mother’s idea of natural childbirth was giving birth without makeup.”

-Robin Williams