Weekly Market Update by Retirement Lifestyle Advocates

Weekly Market Update by Retirement Lifestyle Advocates

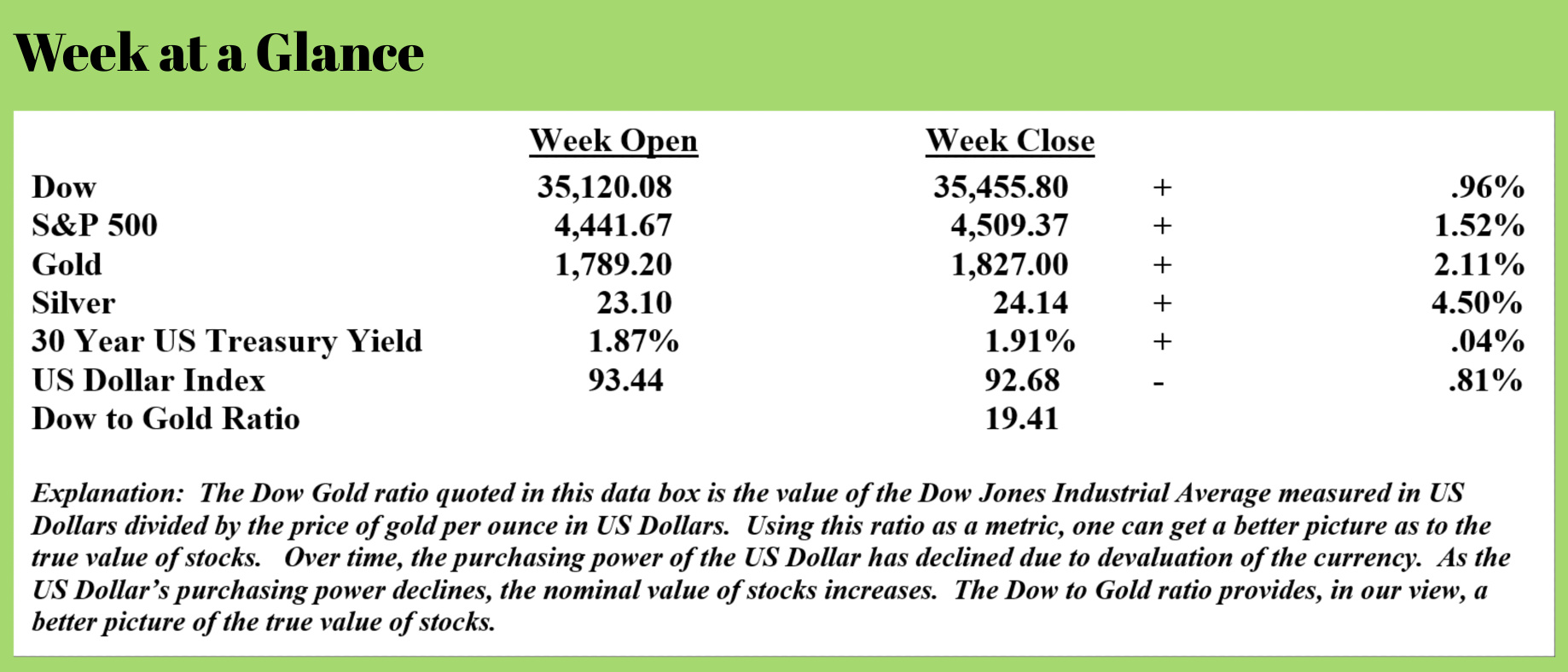

This past week, after the Federal Reserve’s Jackson Hole, Wyoming symposium, Fed Chair, Jerome Powell commented on Fed policy. It was widely anticipated that the Fed Chair would discuss the ‘taper’, or the Fed’s plan to slow the rate at which currency is being created.

The Fed Chair, in many respects, disappointed. This is from “Zero Hedge” (Source:https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/dovish-powell-sparks-most-painful-meltup-52nd-record-high-2021):

All that angst and jitters heading into today's Jerome Powell speech, with so many fearing that the Fed Chair would finally make good on urgent warnings from a growing number of Fed speakers that the Fed's easing is causing bubbles across all asset classes - including housing and certainly stocks - and warns traders that the big, bad taper is coming, and... nothing.

Instead, Powell was far more dovish than almost anyone had expected, barely mentioning the upcoming taper (and only in the context of what the Fed said in the recent Minutes), while reserving the bulk of his speech to discuss why inflation is transitory.

Predictably, Powell's dovishness sparked a waterfall in the dollar and yields, with the 10Y and the Bloomberg Dollar index both sliding.

I have long been of the strong opinion that it will be difficult for the Fed to ‘taper’. Not because of economic reasons, but because of political reasons. Ryan McMaken, of the Mises Institute, wrote an excellent piece on this topic that explains:

Much of the discussion over the Fed’s policies on interest rates tends to focus on how interest rate policy fits within the Fed’s so-called dual mandate. That is, it is assumed that the Fed’s policy on interest rates is guided by concerns over either “stable prices” or “maximizing sustainable employment.”

This naïve view of Fed policy tends to ignore the political realities of interest rates as a key factor in the federal government’s rapidly growing deficit spending.

While it is no doubt very neat and tidy to think the Fed makes its policies based primarily on economic science, it’s more likely that what actually concerns the Fed in 2021 is facilitating deficit spending for Congress and the White House.

The politics of the situation—not to be confused with the economics of the situation—dictate that interest rates be kept low, and this suggests that the Fed will work to keep interest rates low even as price inflation rises and even if it looks like the economy is “overheating.” If we seek to understand the Fed’s interest rate policy, it thus may be most fruitful to look at spending policy on Capitol Hill rather than the arcane theories of Fed economists.

Why Politicians Need the Fed to Keep Deficit Spending Going—at Low Rates

Federal spending has reached multigenerational highs in the United States, both in raw numbers and proportional to GDP.

If all this spending were just a matter of redistributing funds collected through taxation, that would be one thing. But the reality is more complicated than that. In 2020, the federal government spent $3.3 trillion more than it collected in taxes. That’s nearly double the $1.7 trillion deficit incurred at the height of the Great Recession bailouts. In 2021, the deficit is expected to top $3 trillion again.

In other words, the federal government needs to borrow a whole lot of money at unprecedented levels to fill that gap between tax revenue and what the Treasury actually spends.

Sure, Congress could just raise taxes and avoid deficits, but politicians don't like to do that. Raising taxes is sure to meet political opposition, and when government spending is closely tied to taxation, the taxpayers can more clearly see the true cost of government spending programs.

Deficit spending, on the other hand, is often more politically feasible for policymakers, because the true costs are moved into the future, or they are—as we will see below—hidden behind a veil of inflation.

That’s where the Federal Reserve comes in. Washington politicians need the Fed’s help to facilitate ever-greater amounts of deficit spending through the Fed’s purchases of government debt.

Without the Fed, More Debt Pushes up Interest Rates

When Congress wants to engage in $3 trillion dollars of deficit spending, it must first issue $3 trillion dollars of government bonds.

That sounds easy enough, especially when interest rates are very low. After all, interest rates on government bonds are presently at incredibly low levels. Through most of 2020, for instance, the interest rate for the ten-year bond was under 1 percent, and the ten-year rate has been under 3 percent nearly all the time for the past decade.

But here’s the rub: larger and larger amounts put upward pressure on the interest rate—all else being equal. This is because if the US Treasury needs more and more people to buy up more and more debt, it's going to have to raise the amount of money it pays out to investors.

Think of it this way: there are lots of places investors can put their money, but they'll be willing to buy more government debt the more it pays out in yield (i.e., the interest rate). For example, if government debt were paying 10 percent interest, that would be a very good deal and people would flock to buy these bonds. The federal government would have no problem at all finding people to buy up US debt at such rates.

Politicians Must Choose between Interest Payments and Government Spending on "Free" Stuff

But politicians absolutely do not want to pay high-interest rates on government debt, because that would require devoting an ever-larger share of federal revenues just to paying interest on the debt.

For example, even at the rock-bottom interest rates during the last year, the Treasury was still having to pay out $345 billion dollars in net interest. That’s more than the combined budgets of the Department of Transportation, the Department of the Interior and the Department of Veterans Affairs combined. It’s a big chunk of the full federal budget.

Now, imagine if the interest rate doubled from today's rates to around 2.5 percent—still a historically low rate. That would mean the federal government would have to pay out a lot more in interest. It might mean that instead of paying $345 billion per year, it would have to pay around $700 billion or maybe $800 billion. That would be equal to the entire defense budget or a very large portion of the Social Security budget.

So, if interest rates are rising, a growing chunk of the total federal budget must be shifted out of politically popular spending programs like defense, Social Security, Medicaid, education, and highways. That’s a big problem for elected officials because that money instead must be poured into debt payments, which doesn’t sound nearly as wonderful on the campaign trail when one is a candidate who wants to talk about all the great things he or she is spending federal money on. Spending on old-age pensions and education right now is good for getting votes. Paying interest on loans Congress took out years ago to fund some failed boondoggle like the Afghanistan war? That’s not very politically rewarding.

So, policymakers tend to be very interested in keeping interest rates low. It means they can buy more votes. So, when it comes time for lots of deficit spending, what elected officials really want is to be able to issue lots of new debt but not have to pay higher interest rates. And this is why politicians need the Fed.

The Fed Is Converting Debt into Dollars

Here’s how the mechanism works.

Upward pressure on rates can be reduced if the central bank steps in to mop up the excess and ensure there are enough willing buyers for government debt at very low-interest rates. Effectively, when the central bank is buying up trillions in government debt, the amount of debt out in the larger marketplace is reduced. This means interest rates don't have to rise to attract enough buyers. The politicians remain happy.

And what happens to this debt as the Fed buys it up? It ends up in the Fed’s portfolio, and the Fed mostly pays for it by using newly created dollars. Along with mortgage securities, government debt makes up most of the Fed’s assets, and since 2008, the central bank has increased its total assets from under $1 trillion dollars to over $8 trillion. That’s trillions of new dollars flooding either into the banking system or the larger economy.

For years, of course, the Fed has pretended that it will reverse the trend and begin selling off its assets—and in the process remove these dollars from the economy. But clearly, the Fed has been too afraid of what this would do to asset prices and interest rates.

Rather, it is increasingly clear that the Fed’s purchases of these assets are really a monetization of debt. Through this process, the Fed is turning this government debt into dollars, and the result is monetary inflation. That means asset price inflation—which we’ve clearly already seen in real estate and stock prices—and it often means consumer price inflation, which we’re now beginning to see in food prices, gas prices, and elsewhere.

This week’s radio program features an interview with best-selling author and economist, Harry Dent. I caught up with Harry from his home in Puerto Rico and got his take on current market conditions as well as his forecast for traditional investments like stocks and bonds moving ahead.

You’ll want to catch this conversation by listening to the podcast now. Just link the tab labeled "Podcast" at the top of this page to enjoy a great conversation with this week's guest, Harry Dent.

“Happiness is nothing more than good health and a bad memory.”

-Albert Schweitzer