Weekly Market Update by Retirement Lifestyle Advocates

Weekly Market Update by Retirement Lifestyle Advocates

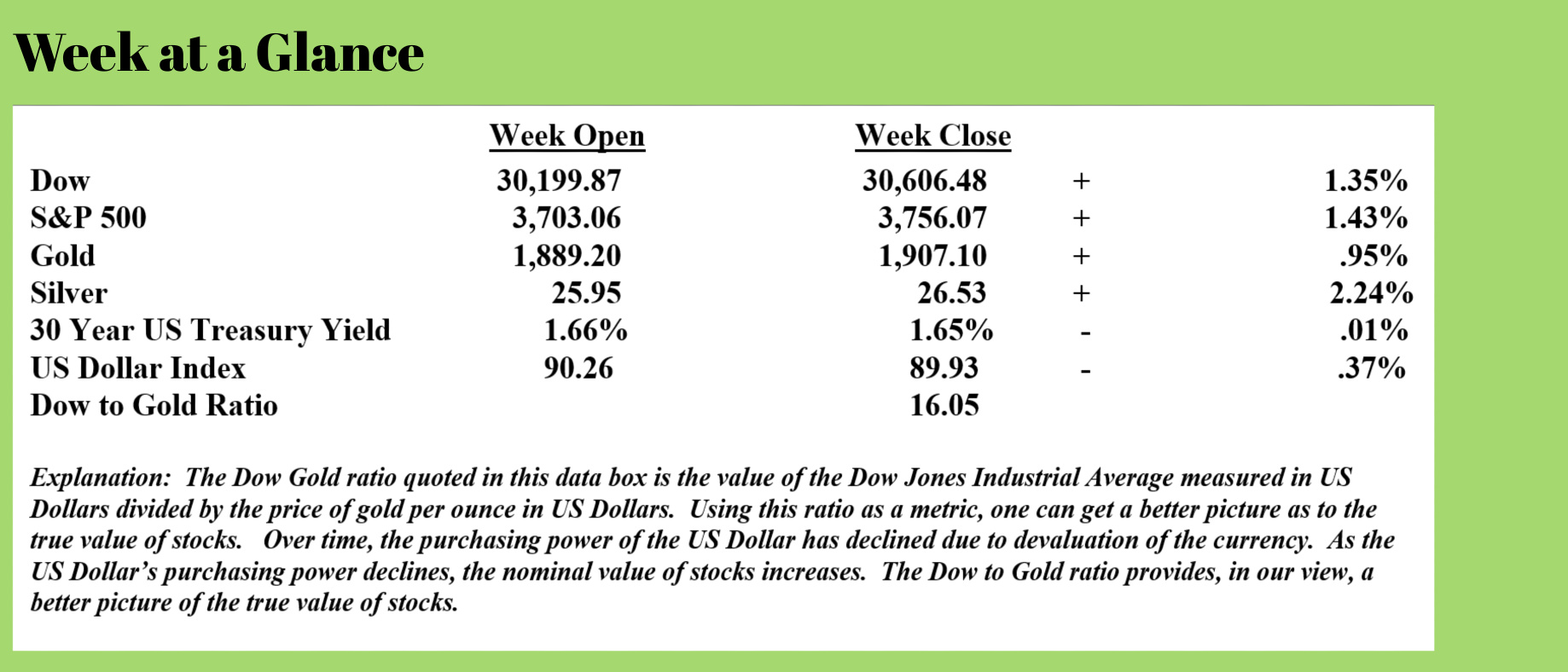

Stocks and precious metals rallied going into year-end last week. The US Dollar continued its decline.

Stocks remain overbought although they can remain overbought for quite a long period of time. Fed policy remains extremely accommodative and a continued rally in stocks and metals is possible due to money creation.

In the January “You May Not Know Report” to be mailed mid-month, I discuss the predictable outcomes of money printing in detail and offer strategies for you to consider in your own, personal financial situation.

While price inflation is the first inflation end result that most of us think about when we consider the effect that money creation will have on our economy and society, history teaches us that the wealth gap and resultant social unrest followed by a reset are also inevitable outcomes of money creation.

History also teaches us that as money creation becomes the mainstream, “go-to” policy, it accelerates exponentially.

Past radio program guest, Dr, Chris Martenson describes the path to hyperinflation using an analogy of water drops in Yankee Stadium. I have borrowed his analogy to describe this phenomenon in past issues of “Portfolio Watch”.

If you began by placing a drop of water in Yankee Stadium and then every minute that passed doubled the drops deposited in the stadium one minute earlier, you’d fill the entire stadium in less than one hour.

To make the point, you’d put one drop in the stadium immediately. After one minute passed, you put in 2 drops, after another minute passes 4 drops, and so on.

Interestingly, five minutes after the bases were covered the stadium would be full. In other words, most of the action takes place in the last few minutes.

Hyperinflations work similarly. Most of the action takes place at the end.

When you analyze the numbers, you have to seriously wonder if we are near the end. Follows is an excerpt written by Pascal Hugli that was published on Mises (emphasis added):

Although monetary policy had been ultra expansionary even well before the virus hit the world, central bankers are currently upping the ante once again. While it took the Federal Reserve almost six years to create 3.5 trillion in new US dollar liquidity, this time around it took only ten months to unleash a monetary tsunami of $3 trillion with the projection of at least another $1.8 trillion next year.

While these astronomical numbers don’t really speak to the general public anymore, another astonishing fact resonated with them: after March 2020 alone, the US banking system is reported to have increased the M1 money supply by 37 percent. What this means in plain words is that 37 percent of all outstanding dollars and dollar bank deposits that have ever existed have been created this year. If one bears in mind that monetary aggregates like M0, M1, and M2 today no longer give an accurate account of all the money in the system because they do not account for the shadow banking’s collateral multiplier, one can only guess that the actual extent of monetary expansion must be a lot greater.

Financial markets have gone crazy. Not only do Swiss and German bonds have a negative interest rate, but the Spanish ten-year bond also recently dipped into negative territory for the first time, albeit for a brief period. Buying these new zero-to-negative-yield bonds is the European central bank (ECB), as an analysis by Germany’s DZ Bank shows.

The European bond is on the verge of vanishing. Just as Europe will gradually follow in Japan’s footsteps and increasingly experience the social consequences of zero interest rates, its bond market is being “japanified.” The Bank of Japan (BOJ) has long been overtaken by the fate of being virtually the sole bidder on Japan’s government bonds (JGB). The ECB is currently facing the same risk, and there really seems to be no way out of it. Just as has been the case in Japan, Europe’s central bankers are siloing ever more government bonds, depriving the private sector of this “high-powered” collateral and making monetary policy ever more difficult. In this regard too, Mises’s famous spiral of intervention will keep on spinning as technocrats and apparatchiks have to come up with new out-of-the-box “solutions.”

I alluded to the social consequences of money creation above. As devastating as price inflation is to savers and investors, the little-discussed social consequences of money creation are every bit as costly, perhaps even more costly from some perspectives.

Mr. Hugli commented on these social consequences of money creation in an article he published in July. Here is a bit from that piece (emphasis added):

Anyone who has ever been to Japan knows: Japan is special. The country has many strange habits. The Japanese culture is simply different and many peculiarities are hardly understood in the West.

But it's not only the old established traditions that are foreign to us Westerners. Just as disturbing are social developments such as the increasing tendency of Japanese people to overwork, parasite singles who isolate themselves, or the existence of platonic relationships in which people are paid to hold hands. All of these phenomena are indeed odd and are generally attributed to the peculiar Japanese culture. However, few people are aware that there is probably a deeper reason for these curiosities, namely an economic one: zero and negative interest.

Mr. Hugli notes that from the 1960’s through the 1980’s, Japan was an economic powerhouse. However, beginning in the 1990’s as interest rates moved lower to create more money (money is loaned into existence in a fractional reserve banking system so lower interest rates mean more money creation. Money creation typically only begins when lower interest rates no longer creates the desired quantity of new money), Japan began to change economically and socially. Here are some of Mr. Hugli’s comments (emphasis added):

At the beginning of the 1990s, the interest rate policy in Japan increasingly moved toward the zero lower bound. Three decades later, the country is still stuck in a zero interest rate trap and the magic and innovative power of Japanese companies have diminished considerably. In the international context, they can hardly keep up with American or Chinese counterparts, or at least they are no longer as feared as they used to be.

Innovation ultimately has a lot to do with time preference in economic terms. Real innovations often only pay off years later, which is why innovative companies have to be prepared for a long haul. Zero-interest rates counteract the power of innovation because they almost always go hand in hand with higher time preference. The fact that Japanese companies are hardly feared by global competition today is probably largely due, albeit not monocausally, to Japan's long-standing zero interest rates.

Today, people generally speak of the lost decades that Japanese companies have fallen victim to. The opportunity costs of this zero-interest-rate policy are also reflected in the dwindling innovative strength and productivity. It is hard to imagine where Japan would be today if the Japanese economy had been spared the burden of zero and negative interest rates.

Mr. Hugli notes that Japan’s innovations have come in rather bizarre fields; platonic relationship offers, dolls to serve as companions and relationship substitutes and a new emerging market is renting a substitute father or friend. If you don’t want to go out alone, you can rent a companion or you can rent a whole family to be able to fake enough celebrants at your personal graduation party. Hugli also notes the widening wealth gap in Japan (emphasis added):

Younger people in particular have been hit the hardest. As recently as 1992, 80 percent of young Japanese workers had a regular job. In 2006, half of all young workers were in part-time jobs with lower wage levels. Only 2 percent of nonregular workers in Japan move to regular work each year. Most of today's young workers are unlikely to find a regular job.

Quite a few young people have therefore completely cut themselves off from the world of work, an inglorious trend known in Japan under a popular term called hikikomori. At the same time, people are withdrawing more and more from civil society and the public sphere into their own four walls. Unofficial speculations suggest that this phenomenon, described as cocooning, now affects up to 10 million Japanese.

Zero and negative interest rates are a reality in Europe and will soon be in the US as well. It should not be expected that we will necessarily be immune to similar developments to those in Japan. In the West, the first "signs of resignation" are beginning to appear, particularly among millennials and younger generations. A growing proportion of them seems to be subconsciously realizing that they have to adjust to an increasingly stagnant life.

The anger and frustration are then directed either at the condemned turbocapitalism, against which more and more people take to the streets in demonstrations.

Thank you all for your continued support and referrals. If you are not participating in our weekly Monday update webinars, you can get more information on them at www.RetirementLifestyleAdvocates.com or catch the replays there.

If you need more information about the webinars or would like to schedule a phone conversation to discuss precious metals or tax planning, just give the office a call at 1-866-921-3613.

This week’s radio program features an interview with author, frequent television and radio commentator John Rubino of www.dollarcollapse.com.

The interview is available at www.RetirementLifestyleAdvocates.com.

“It is a miracle that curiosity survives formal education.”

-Albert Einstein