Weekly Market Update by Retirement Lifestyle Advocates

Weekly Market Update by Retirement Lifestyle Advocates

One of the themes of my “Revenue Sourcing” book is that history repeats itself, or in the words of Mark Twain, at least it rhymes.

Throughout history, whenever debt levels get too high to pay with honest money, policymakers and politicians have resorted to currency creation to attempt to put a band-aid on a fiscal problem that really requires a tourniquet.

Eventually, one of two things happens. Either the currency creation continues, and the currency is eventually destroyed, or the currency creation stops in time to save the currency, only to see a period of painful deflation materialize.

While it is too early to tell which outcome we might experience and when it might occur, the harsh reality is that the current trajectory of massive deficit spending ($2 trillion last fiscal year) cannot continue.

There is another harsh reality of which you should be cognizant. This massive financial problem can only be solved by austerity – the collective group of politicians in Washington will have to proactively take steps to spend only what is collected in tax revenues. Should this step be taken (which is about as likely as me starting in the NFL), a painful deflationary environment would appear.

Deflation is ugly.

Stocks crash.

Real estate prices plummet.

Unemployment eventually soars.

There is no politician or policymaker that wants to see deflation on their watch. So, the only alternative is more currency creation. Which creates a prosperity illusion for a while, but ultimately ends up causing inflation, sometimes even hyperinflation.

We’ve all experienced, first-hand, the prosperity illusion that developed after the massive currency creation that began in 2020. Then, after a time lag, inflation emerged in earnest. I write about this in detail in the February “You May Not Know Report” client letter.

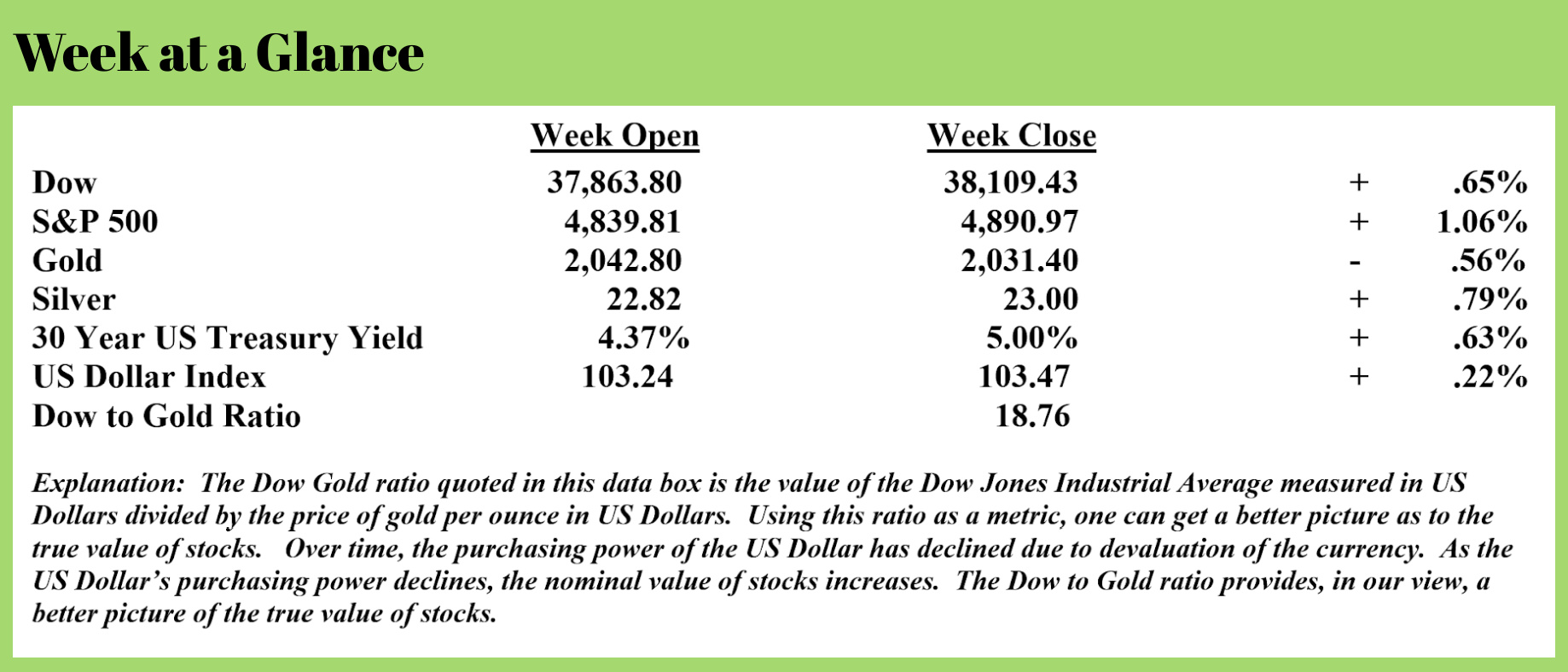

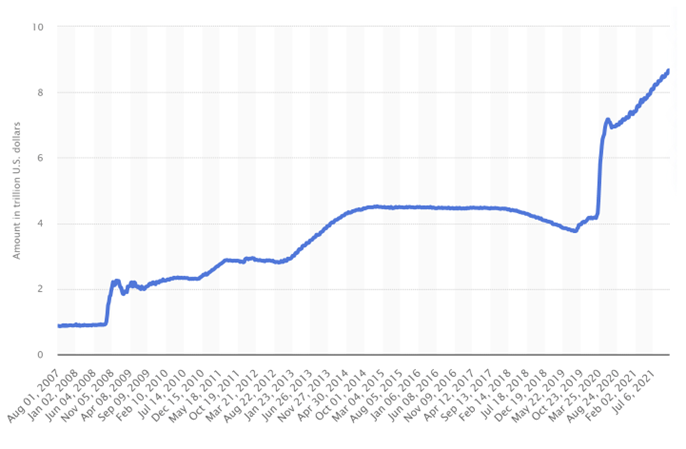

The chart below is an illustration of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet, which is a proxy for the amount of currency created.

The chart below is an illustration of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet, which is a proxy for the amount of currency created.

Notice from the chart that the Fed began currency creation at very high levels in early 2020.

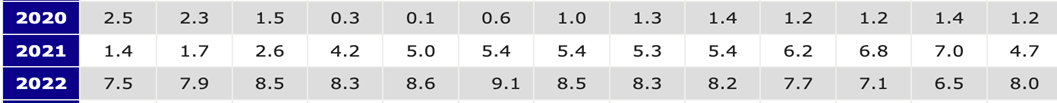

The ‘official’, reported inflation rate is the Consumer Price Index which is a highly “adjusted” (or dare I say manipulated) index. Adjustments are made to this index to make the reported inflation number appear more favorable. These adjustments include substitution, hedonic (pleasure adjustments), and weightings.

While the CPI reported is lower than the actual inflation rate, in my opinion (and nearly everyone else’s), we will use it here to demonstrate the time lag that exists between currency creation and the consequences of that currency creation.

The Federal Reserve balance sheet chart above confirms that currency creation began in early 2020. It was about one year later, in April of 2021, when the CPI jumped from 2.6% to 4.2%; that’s an increase of 61.5% in just one month!

Then, about one year later, in March of 2022, the officially reported inflation rate was 8.5% - double the rate of 11 months prior. Then, by June of 2022, the CPI peaked at 9.1%.

Perhaps we can conclude from this data that there is a 12 to 24-month time lag from the time currency is created until the full effects of that currency creation are felt.

Now, as we are into calendar year 2024, the Fed has once again put rate cuts and easy money policies on the table. It remains to be seen if these policies will ultimately be pursued and, if they are pursued, if they will even work.

At some point, history teaches us that currency creation will have to stop.

Economist Ludwig von Mises described the inevitable outcome of persistent, reckless currency creation. Von Mises developed his theory after witnessing first-hand the German hyperinflation post World War One and an Austrian hyperinflation that stopped before the currency was destroyed. This from Thorsten Polleit on the subject:

In the early 1920s, Ludwig von Mises became a witness to hyperinflation in Austria and Germany — monetary developments that caused irreparable and (in the German case) cataclysmic damage to civilization.

Mises's policy advice was instrumental in helping to stop hyperinflation in Austria in 1922. In his Memoirs, however, he expressed the view that his instruction — halting the printing press — was heeded too late:

Austria's currency did not collapse — as did Germany's in 1923. The crack-up boom did not occur. Nevertheless, the country had to bear the destructive consequences of continuing inflation for many years. Its banking, credit, and insurance systems had suffered wounds that could no longer heal, and no halt could be put to the consumption of capital.

As Mises noted, hyperinflation in Germany was not stopped before the complete destruction of the Reichsmark.

The 20th century saw many hyperinflations, including China in 1949–50, Brazil in 1989–90, Argentina in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Russia in 1992, Yugoslavia in 1994, and, most recently, Zimbabwe in 2006–09. All of these hyperinflations were the direct result of a system of unfettered fiat money under government control — a system that produces money in a non-market-conforming way: the money supply is increased out of thin air by banks simply extending loans (circulation credit) and/or monetizing assets.

According to the Austrian school, money is, like any other good, subject to the irrefutably true law of diminishing marginal utility. It is this law, which is implied by the axiom of human action, which is at the heart of Mises's praxeology. As it relates to money, the law of diminishing marginal utility states that an increase in the quantity of money by an additional unit will inevitably be ranked lower (that is, valued less) than any same-sized unit of money already in an individual's possession. This is because the new money can only be employed as a means for removing a state of uneasiness that is deemed less urgent than the least-urgent uneasiness which one has up to now been removing with the money in one's possession.

People hold money because money has purchasing power (which people desire, given the fact of uncertainty as an undeniable category of human action), and the purchasing power of money is determined by the supply of and demand for money.

If a rise in the money supply is accompanied by an equal rise in money demand, overall prices and the purchasing power of money remain unchanged. Once people start to exchange their increased money holdings against other goods, however, prices will start to rise, and the purchasing power of money will fall. That said, it is rise of the money supply relative to the demand for money that brings to the fore the obvious effect of an increasing money supply: rising prices.

Mises saw that money demand plays a crucial role for the possibility of an unfolding hyperinflation. If the central bank is expected to increase the money supply in the future, people can be expected to rein in their money demand in the present — that is, increasingly surrendering money against vendible items. This would, other things being equal, drive up money prices. Mises noted that "this goes on until the point is reached beyond which no further changes in the purchasing power of money are expected." The process of rising prices would come to a halt once people have fully adjusted for the expected increase in the money supply.

What happens, however, if people expect that, in the future, the money-supply growth rate will increase to ever-higher rates? In this case, the demand for money would, sooner or later, collapse. Such an expectation would lead (relatively quickly) to a point at which no one would be willing to hold any money — as people would expect money to lose its purchasing power altogether. People would start fleeing out of money entirely. This is what Mises termed a crack-up boom:

If once public opinion is convinced that the increase in the quantity of money will continue and never come to an end, and that consequently the prices of all commodities and services will not cease to rise, everybody becomes eager to buy as much as possible and to restrict his cash holding to a minimum size. For under these circumstances the regular costs incurred by holding cash are increased by the losses caused by the progressive fall in purchasing power. The advantages of holding cash must be paid for by sacrifices which are deemed unreasonably burdensome. This phenomenon was, in the great European inflations of the 'twenties, called flight into real goods (Flucht in die Sachwerte) or crack-up boom (Katastrophenhausse).

Here’s the point.

Currency creation will eventually stop, either proactively or reactively. I’m reminded of the simple yet profound statement made by economist Herbert Stein, who said, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”

Until it does, you’d be wise to consider an inflation hedge in your portfolio as well as assets that will perform well in a deflationary environment.

The radio program this week once again features a conversation that I did with Murray Gunn, Head of Global Research at Elliot Wave International. I get Mr. Gunn’s forecast for several financial markets and chart with him about the fascinating topic of socionomics.

If you haven't heard the program yet, click on the "Podcast" tab at the top on this page to listen to the show now.

“No matter what people tell you, words and ideas can change the world.”

-Robin Williams

Comments